New Dylan Book Featured in Anglo-Celt Story

© Ted Russell

Bringing it all back home

By Damian McCarney

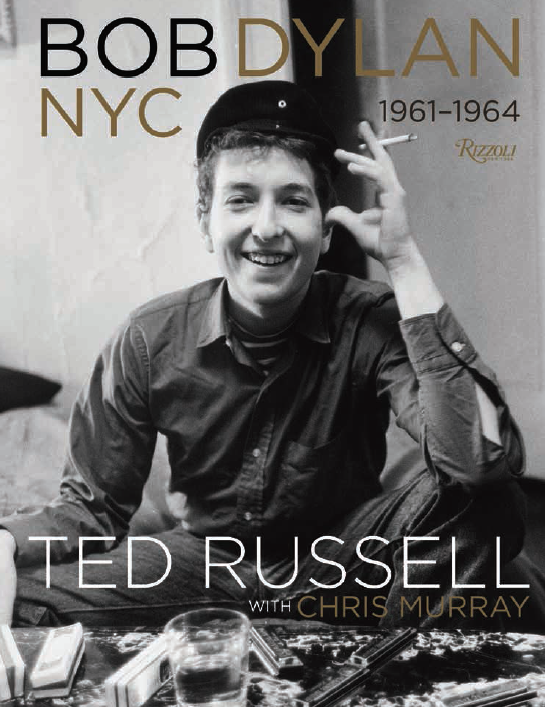

Corduroy cap perched on his head, smoldering cigarette in hand, a youthful, toothy Bob Dylan sits at a marble top table sporting a row of harmonicas smiles up from the cover of a hardback book.

It’s from a collection of black and white stills of Dylan taken by Ted Russell from 1961-64, and never before published. Dylan had only recently ditched his birth name Robert Zimmerman and set off from Hibbing, Minnesota, to try his hand at folk singing in New York City and emulate his hero Woody Guthrie. Albums and world fame weren’t far away, but by no means inevitable.

Asked which photo was his favorite, the book’s co-author Chris Murray commences a leisurely scramble through pages, a snatch of commentary in his half-whispered speech accompanies each momentary pause: “This is a lovely photo”- flick – flick – “One of the typewriter ones” – flick – “The contact sheets are great” – flick – “I like this one a lot, he’s sort of baby faced”.

Sitting in a plush tea-room in the Radisson Farnham, Chris’s enthusiasm for these photos hasn’t dimmed in the few years since he answered the phone to Ted Russell, an elderly gent now, but once a freelance photojournalist who regularly took shots for the likes of Life magazine.

Ted had been impressed by a collection of photos by Alfred Wertheimer of Elvis at 21, which Chris had published, and invited him to peruse his unpublished shots of fresh-faced Dylan. The 8’’ x 10’’ prints and negatives featured four different shoot, including a show at the legendary folk venue Gerde’s where Dylan made his name.

Another session captured Dylan and his first love Suze Rotolo settling into their new apartment. Suze would later share the cover of Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album, nestled into Dylan’s side for warmth as they strolled carefree down a snowy New York street.

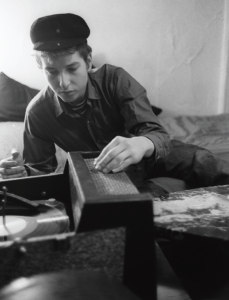

“I see this,” Chris recalls in a reverential hushed tone, and shifting the book around. “I see Bob with the record player, ‘Jesus’. Then I see him at the typewriter and I go, “My God’. And then I see him coming out of the basement of Gerde’s and I’m going, ‘This is history. This is it’. And I know all the Dylan photos because not only am I into championing the genre, I love Bob Dylan more than anyone so I felt like I had discovered hidden gold; the pot of gold at the end of a rainbow.”

Given the cultural colossus that Dylan would become it’s astonishing the photos should remain unpublished, but at the time Dylan was—aside from one glowing review in the New York Times—still largely unknown.

Back in ’61 Ted Russell made the mistake of playing some of Dylan’s demos which would feature in his debut album to the magazine editors when pitching the idea of a photo essay on the struggles of an up-and-coming folk singer trying to make it.

“They thought they were on the wrong speed,” Chris laughs. “They said, ‘Well we like these photos but this guy’s never going to make it, he sounds like a hillbilly!’”

Ted—a jazz aficionado with no interest in folk—shelved the pics and got on with building an illustrious photographic career, which included eight years as cover editor for Newsweek magazine.

Roll on half a century or more and Chris, owner of Govinda Gallery in Washington, D.C., is the go-to man for exhibiting and publishing photos of musical icons. The foundation stone of this reputation was laid when he hosted Annie Leibovitz’s first exhibition of photos in the early 1980s. At that show Chris wisely bought Annie’s famous photo of a naked John Lennon in an almost fetal position wrapped around a passive Yoko Ono. “She [Annie} said, ‘You know John was murdered the day I took that photo’.

“And he was. So I had an epiphany, not only was it a good photo but it was an important photo, and I bought it. I silently said to myself on the spot. I’m going to champion other significant photos like this, particularly of musicians. Rock photography in 1983-84, there was no genre known as rock photography; it was a bastard genre at best. There wasn’t a curator, there wasn’t a gallery, there wasn’t a museum who was showing it or giving it any respect.”

Chris was compelled to find other photographers—those behind the album covers, which had so mesmerized him. As a result, Govinda Gallery has hosted exhibitions and published photobooks depicting everyone from the King to the Boss.

Russell shunned flashes when capturing these candid moments of manish boy Bob finding his feet, instead shooting only in available light. Therefore Bob Dylan NYC 1961-1964 features images of varying quality, but for Dylan’s fans it’s all gold. After the Celt insists he’s only permitted to choose one favourite, Chris further deliberates.

“I love this photo for a number of reasons,” he says finally settling his mind. “First of all it captures the intimate scenario of Bob before he’s famous at his first apartment, just relaxed as anyone would have been in those days, playing a record. I love it because of the record player. You see Bob learned a lot of material from listening to vinyl… I identify with this old turntable, I can see the sparkly kind of fabric they used to have, and I like the fact that Bob is listening to a record, perhaps learning a song—that’s what this era was about. It’s about a folk musician who’s transforming the genre.

“Bob became such an important persona that every photographer did eventually photograph him, from Richard Avedon to Andy Warhol but here you see him at the start, at the genesis. I love it as an intimate document of America’s greatest songwriter of our time—there’s no question about it.”