The Washington Post review of Donovan’s Sapphograph exhibition by Mark Jenkins

Mark Jenkins wrote a compelling and in-depth review of Donovan’s exhibition of his Sapphographs now on view at Harvard University’s Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington, D.C. We present that review in its entirety here. The exhibition is a remarkable one as is the gallery at the Center for Hellenic Studies. The exhibition continues through March 31.

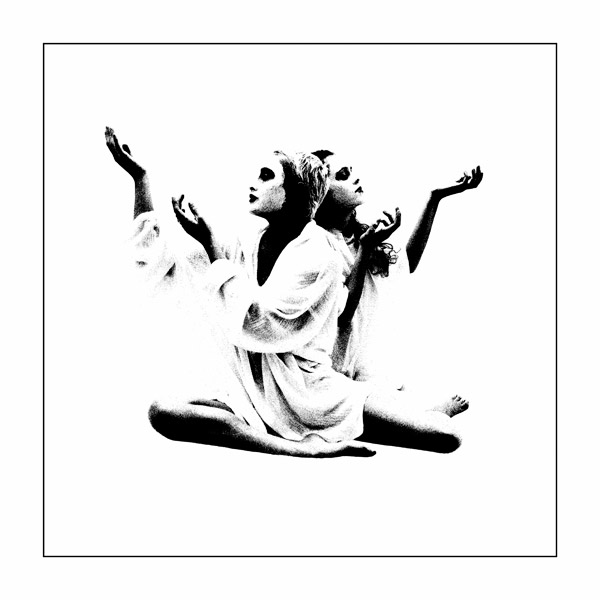

Supplication © Donovan

Supplication © Donovan

From ‘Mellow Yellow’ to black and white

By Mark Jenkins

January 20, 2016

With their simplified images and large expanses of white, the “Sapphographs” on display at the Center for Hellenic Studies have a pop-art blankness. But these high-contrast pieces, based on photos made in the late ’90s, are loaded with associations for their maker, veteran folk-rocker Donovan.

The pictures are named for Sappho, the 7th-century-B.C. poet whose identity also is largely blank. Little is known about her life, and only fragments of all but one of her poems exist today. (The bard’s name — probably pronounced “Psap-foh” in her time — is the source of the word “sapphic,” and her home island, Lesbos, yielded the term “lesbian.” But her sexuality is a matter of conjecture.)

To Donovan, 69, who was born in Scotland and now lives in Ireland, Sappho’s poetry is linked to his own Celtic tradition. It also represents a golden age when all the arts were entwined. In ancient Greece, “poetry, music and drama were one,” the musician said while leading a recent tour of his artwork at the center’s secluded campus a few blocks off Embassy Row in Northwest Washington.

Sappho’s verse was revered in the ancient world and seems to have been widely known. Bits of it continue to turn up in such unexpected places as the paper wrapping on mummies. “It’s very pop,” said Donovan, who noted that ancient bards sang their verse and that Sappho probably played a small harp.

The singer-songwriter did his bit to make Sappho pop by recording the song “Be Mine,” whose lyrics were adapted from the poet’s, for his 1996 album, “Sutras.” Inspired by that experience, he began the experiments that led to the Sapphographs. (The word “lyric,” by the way, derives from the lyre, another Greek stringed instrument.)

Donovan had sojourned off and on in rural Greece, whose sunshine, solitude and bardic tradition inspired him, for decades before starting his Sapphographs. He was lying low there in 1966, after a marijuana bust that he says was a setup, when he learned that his “Sunshine Superman” was a No. 1 hit. But the light-blasted Sapphographs are a result of the California sun.

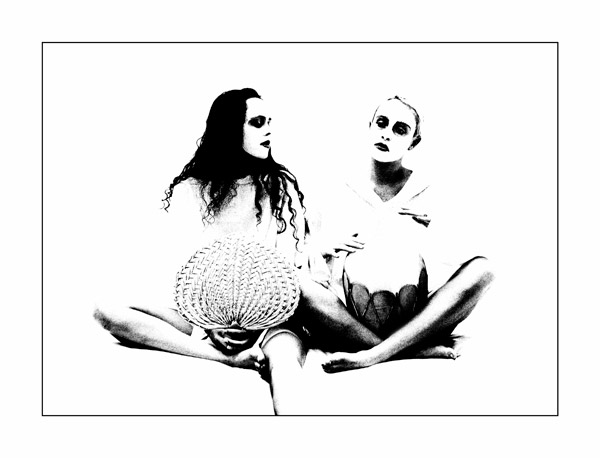

The singer rented an unfurnished 1940s mansion in Zuma Beach for a photo shoot. “It was nothing but white space and pure light,” he recalled. Using a Rolleiflex film camera and natural light, he began making pictures of his wife, Linda, his daughter Oriole and her friend Lizzie. He asked them to “dress as if it was a Greek play in 1928,” with flowing white robes and white makeup reminiscent of silent films. Later, he also photographed his daughter Astrella and grandson Sebastian, then a young boy but now old enough to be his grandfather’s tour manager.

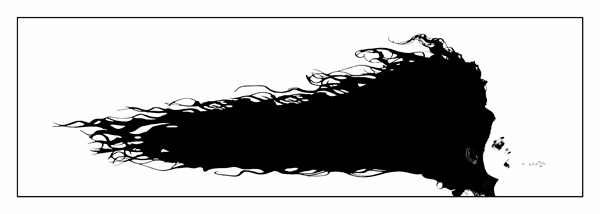

Sappho’s Song © Donovan

Sappho’s Song © Donovan

His inspirations were mostly classical myth and art, and included the near-translucent whiteness of ancient marble statuary. But Donovan also was influenced by Man Ray’s Rayographs, made by placing objects directly on photographic paper, and by Cindy Sherman’s elaborately posed stills from movies that don’t actually exist.

This is most clear from such theatrically posed pictures as “The Supplication,” which looks less like 1928 than the late 1960s, the period of Donovan’s greatest visibility. People have imagined Sappho as many people, so why not as the leader of a hippie mime troupe?

To boost contrast, the musician-photographer experimented with Xerox machines. He wondered, “Can we black the blacks and white the whites? And keep doing it until something disappears?”

That quest led Donovan, ultimately, to Washington. A longtime friend, Govinda Gallery’s Chris Murray, introduced him to local fine-art printmaker David Adamson, who was able to produce the desired deep blacks and hot whites, and on a large scale.

Size is certainly part of the power of these stark images, especially “Sappho’s Song.” The 12-foot-wide picture is mostly a black mane, streaming back from a small face. It suggests a storm, a torrent or even a Medusa-like mass of writhing snakes.

But perhaps the swirling black represents a sound, a possibility suggested by the other element in the composition: a string of alphas and omegas that emanates from the woman’s mouth. Since they begin and end the Greek alphabet, the two letters are often used to symbolize birth and death, commencement and culmination. They also can be seen, or heard, as musical: a primal ah-oh-ah-oh chant.

In another crypto-portrait of a woman whose face is lost to time, the poet’s eyes look left, in the direction of a scrap of text. It’s a morsel, and all that survives, of a Sappho poem. “Sapphographs” is the product of many enthusiasms, but first and foremost the ancient words.

Sappho’s Drum © Donovan

Sappho’s Drum © Donovan

If you go

Donovan’s Sapphographs

The Center for Hellenic Studies, 3100 Whitehaven St. NW.

202-745-4409. chs.harvard.edu.

Dates: Weekdays 10 a.m. to noon and 2 to 4 p.m. through March 31.

Prices: Free.