Roberto Salas, Legendary Cuban Photographer

Copyright © Govinda Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved. Photographer Roberto Salas with Govinda Gallery director Chris Murray, Havana, Cuba 2004.

Copyright © Govinda Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved. Photographer Roberto Salas with Govinda Gallery director Chris Murray, Havana, Cuba 2004.

Much has been written about Cuba recently, with a lot of attention on Jay-Z and Beyonce’s recent visit to celebrate their fifth wedding anniversary. Govinda Gallery has enjoyed an ongoing cultural exchange with Cuba for over ten years, having organized several exhibitions both here in Washington and in Havana. In 2003 we hosted our second exhibition featuring Cuban photography at Govinda Gallery presenting the remarkable photographs of Roberto Salas. Washington Post art critic Jessica Dawson reviewed the exhibition alongside that of White House photographer Diana Walker’s photographs. Here is that review from the Govinda Gallery archives featuring two of the photos described in the story.

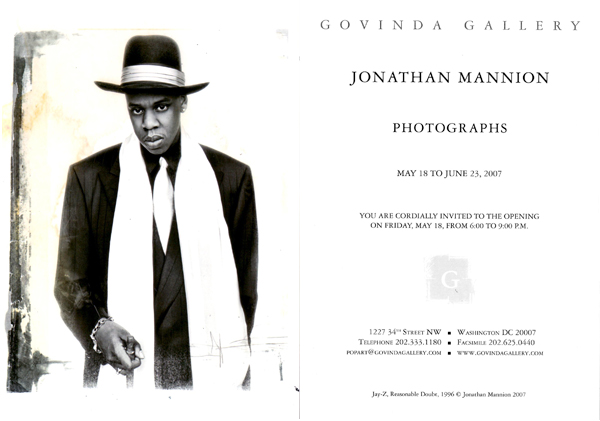

Jay-Z’s just penned song “Open Letter”, his response to the brouhaha surrounding his visit to Cuba, is simply brilliant. Jonathan Mannion’s Reasonable Doubt portrait of Jay-Z from 1996 was featured on the invitation card to his one-person show at Govinda Gallery in 2007.

Roberto Salas’ and Jonathan Mannion’s photographs are available through Govinda Gallery.

Galleries

Shadow and Light: Politics, Photographed

By Jessica Dawson

Thursday, July 24, 2003

Photojournalists claiming to capture a politician’s private moments are kidding themselves—and us. Private moments, by definition, don’t include professional acquaintances. Likewise, exhibitions touting behind-the-scenes access rarely deliver the promised crumbs of intimacy. Which is a good thing for politicians and a bad thing for gallery-goers. The famous remain enigmas, preserving their attraction and our ability to project onto them desires, longings, and animosities. (If we really, truly knew them, would we still care?) In remaining mysterious, though, politicians, and pictures of them, won’t allow us the connection we yearn for. They fail to satisfy the very need that brought us into the gallery in the first place.

Two shows on view now, while documenting very different regimes—photographer Roberto Salas captured revolution-era Cuba; former White House photographer Diana Walker chronicled American presidencies—leave the same dissatisfied aftertaste. As viewers of these pictures, we run up against the dense and sturdy walls erected, by necessity, of public figures. No matter how long and hard photographers shoot at the barricades, they’re not coming down.

In Cuba, photography was to the revolution what socialist realism was to the Soviets—propaganda. Fidel Castro and Che Guevara co-opted young Roberto Salas, who along with his father, Osvaldo, returned to Cuba soon after the revolution sent Fulgencio Batista packing.

Both became part of Castro’s entourage and his coterie of court photographers. Govinda Gallery shows a selection of Roberto’s work documenting the earliest days of the regime, along with a pair of pictures by his father. (The show’s second half consists of recent, treacly nudes, confirming that Roberto is best off sticking to photojournalism.) Castro loved mugging for the camera. He also knew that images could bolster and cement the work of the revolution on an island where pictures traveled farther and wider than words. The Salas show at Govinda proves just how effectively the dictator courted and wooed attention. Much of the time, it seems the artist on view here is Castro (and sometimes, less skillfully, Che). The work of Castro, a master manipulator of the image, pre-dates that of both Warhol and Madonna.

Copyright © Roberto Salas. All Rights Reserved. Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, Palace of the Revolution, Havana, Cuba, January 1959.

Copyright © Roberto Salas. All Rights Reserved. Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, Palace of the Revolution, Havana, Cuba, January 1959.

And it seemed that Salas’s assignment became showing the revolutionaries at turns virile, warm and authoritative. A photo here of Castro lounging in a hammock and sucking a cigar reminds me of a young Mick Jagger preening for the camera. This guy doesn’t just feed of attention, he ignites it. One has the sense, seeing the few pictures at Govinda, that Roberto and Osvaldo Salas were totally captivated by their leaders and swept up in a very powerful and muscular political machine.

Diana Walker succumbed to her subjects’ charisma in much the same way. For two decades beginning in the late 1970s, while working as Time magazine’s White House

photographer, she had access to five presidents. In the introduction to her recent book, “Public & Private: Twenty Years Photographing the Presidency,” from which the 27 pictures at Strand on Volta were culled, the photographer finds herself in full bipartisan gush. Of Ronald Reagan’s kindness in offering a second photo opportunity after Walker missed the first, she says, “How grand he was to do that.” Of Bill Clinton’s introduction of Walker to Nelson Mandela, she writes, “It was an extraordinary kindness of President Clinton, simply out of the blue.” To read these passages, you might mistake Walker for a schoolgirl in love.

And the pictures she has taken don’t offer much in the way of new insights. No matter that she caught Bill caressing Hillary’s forehead. No matter that she caught Reagan doubled over with mirth at a White House cocktail party. Even these so-called private moments—at Strand on Volta, the selections are predominantly from the Clinton years—have a distinctly public feel. A couple of unscripted guffaws or an unusual camera angle (Walker likes to frame her subjects from behind) aren’t particularly revelatory. They are documents of political performance. If Walker thinks she’s showing us something new, she’s been conned and smitten. The pictures produced by Salas and Walker illuminate the uneasy path all journalists negotiate. Is it their publications, and, in turn, their readers, to whom they owe allegiance? Yes, absolutely. But they’ve got to really love what they’re photographing to devote their professional lives to it. Too bad that at times, Walker’s and Salas’s infatuation with their subjects produced something more like glorified fan club pictures.

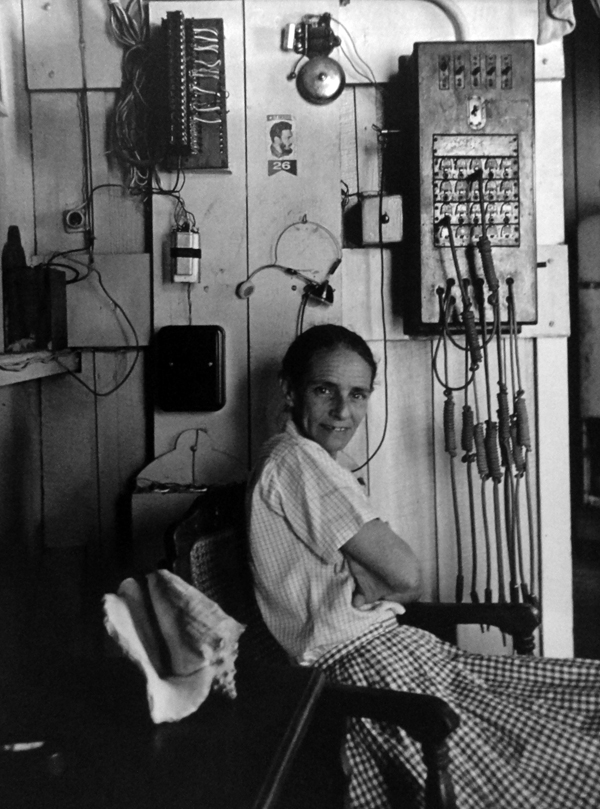

So what about the people who visit galleries to see art that speaks to us about ourselves and about being human? There’s one black-and-white picture at Govinda that might satisfy. In among a small selection of Salas’s touristy shots that hang alongside the political pieces is a picture of a woman named Lola who, in 1965, operated the telephones at the Matahambre copper mines. Outfitted in a gingham skirt and checkered shirt, she gives a gapped-toothed smiles registering both playfulness and resignation. Hers is a face like the ones Dorothea Lange shot for the Farm Security Administration—creased, but registering the passage of time as surely as the striations on an Arizona cliff. Transcending circumstance and politics, the picture steps from journalism into art. It’s the best thing here.

Copyright © Roberto Salas. All Rights Reserved. Lola, Matahambre copper mines, Pinar del Rio, Cuba 1965.

Copyright © Roberto Salas. All Rights Reserved. Lola, Matahambre copper mines, Pinar del Rio, Cuba 1965.

Really enjoyed the photo story and reminiscing! Thanks for a walk down Memory Lane!

love roberto salas!! so glad i have a photo of his!