Editor and writer extraordinaire, David Friend, recently wrote a wonderful story on photographer Bob Gruen in Vanity Fair. Govinda Gallery first exhibited Bob’s photographs thirty years ago at a launch for his book with Yoko Ono, Sometime in New York City (Genesis Publications, 1995). Govinda Gallery director, Chris Murray, also brought that exhibition to Fototeca de Cuba in Havana in December 2006. Gruen’s photographs were part of Murray’s first exhibition in Cuba, La Revolucion del Rock & Roll, also at Fototeca de Cuba in 2002. Gruen was also featured in Murray’s book Rolling Stones 40×20 (Insight Editions). Murray talks about Gruen and his photographs in the Vanity Fair story by David Friend.

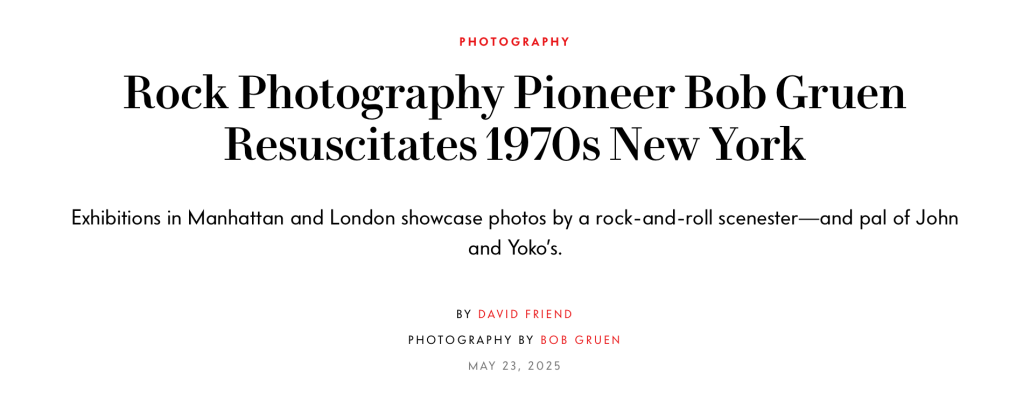

Two new exhibitions celebrate the singular work of photographer Bob Gruen, who, a half century ago, prowled New York’s night spots, making pictures of rising rock-and-rollers, including the young guns of punk rock. At the time, Gruen was merely capturing “the scene.” Today, his images are canonical: John Lennon in a T-shirt emblazoned with “NEW YORK CITY”; Led Zeppelin on the tarmac with their private jet; the Ramones in front of CBGB; Blondie’s Debbie Harry on West 50th Street, pretending to emerge from a car wreck. This month, those classics have graced the walls of two galleries: one show, featuring vintage prints, was part of last week’s Photo London festival; a second is on view through the end of the month at New York’s Music Photo Gallery.

It all started innocently enough. In June 1965, Gruen was a rebellious 19-year-old from Great Neck, Long Island. While attending a sociology class at a Baltimore community college, he was constantly feuding with his professor. At one point, the teacher dismissively told him that he should “go to Greenwich Village and smoke pot with the hippies.” In other words: get lost.

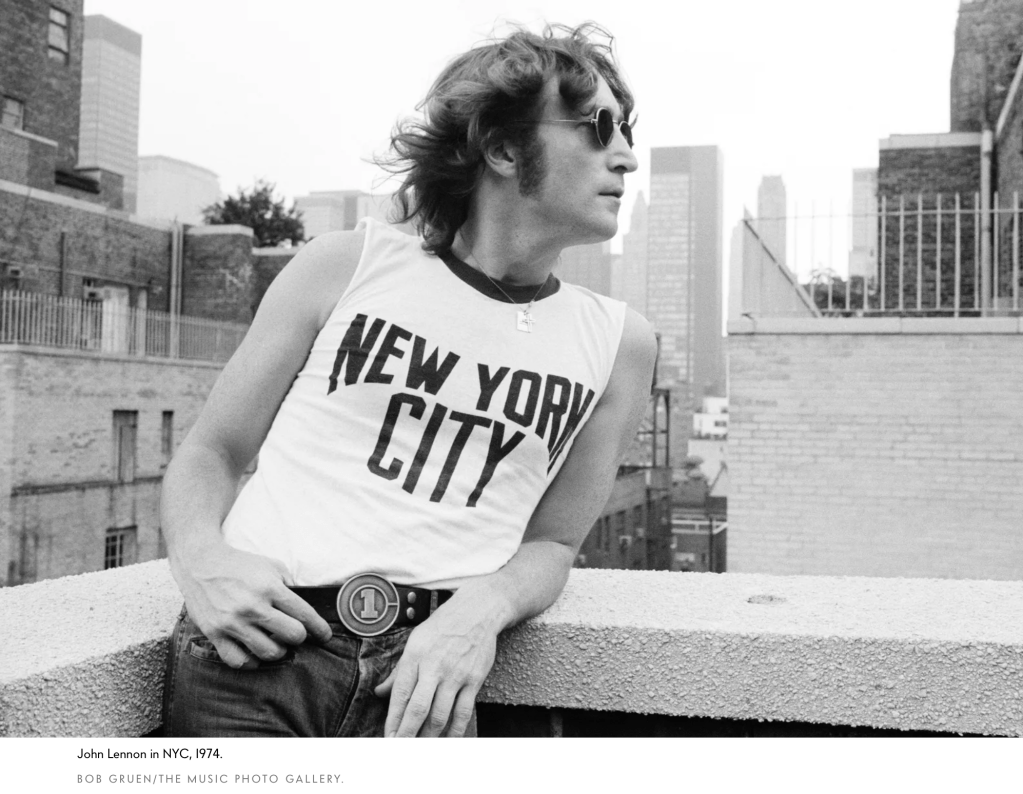

Gruen loved the idea. He packed his camera gear and moved to Manhattan. The following month, he caught a ride to the Newport Folk Festival, where he managed to fire off a few frames as Bob Dylan famously “went electric” (in the now-legendary five-song set depicted in the film A Complete Unknown). Gruen started hanging out at New York rock clubs, recording studios, and dressing rooms. He wheedled stagehands for photo passes. He got to know the promoters and the managers, the roadies and the sound-check guys. He blended in. “I made friends with the bands,” he explained, with delight in his voice. Friends like Ike and Tina Turner. Elton John. Patti Smith. John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten). Iggy Pop. Johnny Thunders. The Clash.

“I literally dragged Bob around by the nape of the neck to parties, to clubs, to concerts because he was starting out,” says Lisa Robinson, now a Vanity Fair contributing editor. At the time, she was running several rock publications with her husband, Richard, and Lenny Kaye. Gruen became the house photographer for their fanzine, Rock Scene. “It was the beginning of the ’70s,” she explains. “There were no guardrails, no publicists. We were all at CBGB every night. I went on tour with Led Zeppelin, and I took Bob to take pictures on the plane. I saw Mick at a party and said, ‘Here’s Bob.’”

Before long, Gruen had befriended John Lennon and Yoko Ono. In 1972, Gruen was photographing an all-night recording session with the couple and their backup band, Elephant’s Memory, at the Record Plant on West 44th Street. At 5 a.m., Gruen recalls, Mick Jagger “came to visit. John [began] showing [Mick] some guitar lines. Yoko had written a song. And the three of them sat down at the piano and sang it.” Gruen snapped several frames, a rare confluence of the three megastars. “I don’t remember the song—it’s bootlegged on the internet somewhere.”

Two years later, when a federal judge began proceedings to deport the ex-Beatle (because of an old marijuana conviction), Gruen came up with a photo idea: “I said, ‘Let’s go down to the Statue of Liberty [to make a picture that] showed America should accept John Lennon.” The result: a symbol-splashed icon of Lennon flashing the peace sign in front of Lady Liberty. “It was a powerful image of personal freedom.” (The case was dismissed in 1975.)

Gruen, without knowing it, was a shining light in what would become a sub-genre: underground rock photography, New York School. Chris Murray, one of the first American gallerists to concentrate exclusively on contemporary music photography, considers Gruen an indispensable chronicler of the street theater and club life central to Manhattan’s rock demimonde during the 1970s and ’80s. “His photos personify New York,” Murray notes. The now ubiquitous photograph of Lennon in the sleeveless tee “became a great emblem of John and of New York. Bob shot a lot of black-and-white—a format that captured the gritty scene and an on-the-streets feeling, and personified downtown music, aesthetically.” Gruen attributes that grainy, rough-hewn look to two factors: “That’s the Tri-X film. But it was also a gritty time.”

The intimacy present in many of his pictures grew out of a deep trust between artist and subject: The musicians, quite simply, considered Gruen a kindred spirit. “The key is access,” says Murray. “Bob himself is a cool guy. He was on the scene. He was a fan. Rock and roll moved him. Hanging out at CBGB, becoming friends with Debbie Harry and David Johansen, they were comfortable with him. He was discreet and very personable and had a lot of hair. He was friends with them on the way up. His skills with the camera—and his not being aggressive—allowed him to be there when these musicians later became superstars. The subjects considered him one of them, just like Elvis got comfortable with Al Wertheimer”—the photographer who caught private moments of a young Presley when he was just starting out.

Gruen’s New York—exhilarating, decadent, black-and-white—has vanished. But one location has remained a North Star for the photographer: his digs. In 1970, a year after his professor told him to scram, Gruen moved into Westbeth Artists Housing, a collection of affordable apartments, lofts, and artist spaces in the West Village. He’s still living there, one of the original tenants.

Robinson looks back with fondness on that slice of urban life and culture, whose energy Lennon channeled in his 1972 live album Sometime in New York City. (Gruen and Yoko later produced a photo book with the same title.) “Everybody knew everybody,” Robinson recalls. “It was a small scene. Kind of like Paris in the ’20s and San Francisco in the ’60s. And, as you know, small scenes don’t last.”

That long-ago scene, however, is still making cameos from time to time. On the walls of galleries, for one, where Gruen’s vintage prints go for a pretty penny. “We had no idea,” Robinson says, “it was going to turn into all this!”

Leave a comment